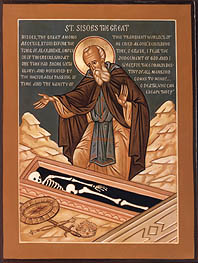

"Sisoes, great among the ascetics, stood before the tomb of Alexander, Emperor of the Greeks, who at one time had shone with glory; and horrified by the inexorable passing of time and the vanity of this transient world, "Lo!" he cried aloud, "beholding thee, O Grave, I fear the Judgment of God and I weep, for the common destiny of all mankind come to mind!... O Death, who can escape thee?"

In its All-Russian Council of the year 2000, the Russian Orthodox Church issued a lengthy document which addressed a number of contemporary issues, and one of them was the issue of artificial life support and euthanasia. Feeding a person, as in the case of Terri Schiavo, is NOT artificial life support. But the question comes, where should the line be drawn. I believe this text did an excellent job of doing just that:

XII. 8. The practice of the removal of human organs suitable for transplantation and the development of intensive care therapy has posed the problem of the verification of the moment of death. Earlier the criterion for it was the irreversible stop of breathing and blood circulation. Thanks to the improvement of intensive care technologies, however, these vital functions can be artificially supported for a long time. Death is thus turned into dying dependent on the doctor's decision, which places a qualitatively new responsibility on contemporary medicine.

Holy Scriptures treats death as the separation of the soul from the body (Ps. 146:4; Lk. 12:20). Thus it is possible to speak about a continuing life as long as an organism functions as a whole. The prolongation of life by artificial means, in which in fact only some organs continue to function, cannot be viewed as obligatory and in any case desirable task of medicine. Attempts to delay death will sometimes prolong a patient's agony, thus depriving him of the right to «honourable and peaceful» death, for which the Orthodox Christian solicit the Lord during the liturgy. When intensive care becomes impossible, its place should be taken by palliative aid (anaesthetisation, nursing and social and psychological support) and pastoral care. All this is aimed to ensure the true humane end of life couched in by mercy and love.

The Orthodox understanding of an honourable death includes preparation for the mortal end, which is considered to be a spiritually significant stage in the life of a person. A patient surrounded with Christian care can experience in the last days of his life on earth a grace-giving change brought about by a new reflection on his journey and penitent anticipation of eternity. For the relatives of a dying man and for medical workers, an opportunity to nurse him becomes an opportunity to serve the Lord Himself. For according to the Saviour's word, «inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it to me» (Mt. 25:40). The attempt to conceal from a patient the information about the gravity of his condition under the pretext of preserving his spiritual comfort often deprives a dying person of an opportunity to be consciously prepared for death and to find spiritual consolation in participation in the Sacraments of the Church. It also darkens his relations with relatives and doctors with distrust.

Death throes cannot be always effectively alleviated with anaesthetics. Aware of this, the Church in these cases turns to God with the prayer: «Give Thy servant dispensation from this unendurable suffering and its bitter infirmities and give him consolation, O Soul of the righteous» (Service Book. Prayer for the Long Suffering). The Lord alone is the Master of life and death (1 Sam. 2:6). «In his hand is the soul of every living thing, and the breath of all mankind» (Job 12:10). Therefore, the Church, while remaining faithful to God's commandment «thou shalt not kill» (Ex. 20:13), cannot recognise as morally acceptable the widely-spread attempt to legalise the so-called euthanasia, that is, the purposeful destruction of hopelessly ill patients (also by their own will). The request of a patient to speed up his death is sometimes conditioned by depression preventing him from assessing his condition correctly. Legalised euthanasia would lead to the devaluation of the dignity and the corruption of the professional duty of the doctor called to preserve rather than end life. «The right to death» can easily become a threat to the life of patients whose treatment is hampered by lack of funds.

Therefore, euthanasia is a form of homicide or suicide, depending on whether a patient participates in it or not. If he does, euthanasia comes under the canons whereby both the purposeful suicide and assistance in it are viewed as a grave sin. A perpetrator of calculated suicide, who «did it out of human resentment or other incident of faintheartedness» shall not be granted Christian burial or liturgical commemoration (Timothy of Alexandria, Canon 14). If a suicide is committed «out of mind», that is, in a fit of a mental disease, the church prayer for the perpetrator is allowed after the case is investigated by the ruling bishop. At the same time, it should be remembered that more often than not the blame for a suicide lies also with the people around the perpetrator who proved incapable of effective compassion and mercy. Together with St. Paul the Church calls us: «Bear one another's burdens, and so fulfil the law of Christ» (Gal. 6:2).