Question: "How do we know whether or not something is dogma if it was not specifically affirmed by an Ecumenical council?"

We have to first consider the question of what we mean by dogma. Usually, in our time, when we speak of dogma we are thinking of formal proclamations of official doctrine, however the word has a wider range of meaning. The word is used by both Philo and Josephus in reference to both philosophical principles and imperial decrees (Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, 2:231). St. Basil the Great used it with reference to the internal teachings of the Church, in contrast with the public preaching of the Church which was intended for those both inside and outside of the Church. He was in a controversy with a group of people who denied that the Holy Spirit was a distinct person of the Godhead, and had argued that this was taught by the doxology: "Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit." His opponents countered that the doxology was not found in Scripture, and so he responded:

"Of the dogmas and preachings [kerygmas] kept safely in the Church, we have some from written doctrine, and some from tradition handed down to us by the Apostles we have received in mystery, both of which have the same validity and force as regards the piety (i.e., the religion); accordingly, no one gainsays these, at least no one that has any experience at all in ecclesiastical matters. For if we should undertake to discard the unwritten traditions of customs, on the score that they have no great force, we should unwittingly damage the Gospel in vital parts.... (D. Cummings, trans., The Rudder of the Orthodox Catholic Church: The Compilation of the Holy Canons, Saints Nicodemus and Agapius (West Brookfield, MA: The Orthodox Christian Educational Society, 1983), p. 853f [emphasis added]).from Canon 91, which is taken from his treatise On the Holy Spirit, 66-67).

St. Basil goes on to cite as examples of the unwritten tradition, the making of the sign of the Cross, baptism by triple immersion, praying while facing east, and the way that the Liturgy is served as examples of unwritten tradition that even the heretics he was arguing with did not dispute.

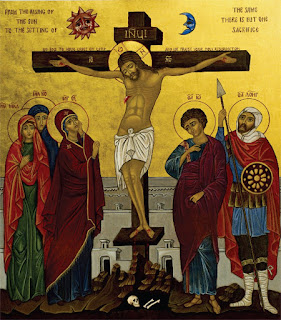

So while dogma, in the sense of official ecumenical decrees has the advantage of being clearly binding upon all in the Church, St. Basil says that the internal teachings of the Church, which have not, at least as of yet, been the subject of official decrees are none the less authoritative. For example, rejecting the use of Christian icons was always heretical, long before the Seventh Ecumenical Council weighed in on the matter. The only difference is that someone who disputed this prior to that Council might be less culpable for their errors than they would have been after it. And, as a matter of fact, holding a heretical opinion is not necessarily a grave personal sin, if one does so in ignorance -- but it certainly becomes one, if such a person refuses the correction of the Church.

The Seventh Ecumenical Council, when it pronounced a series of anathemas directed at the Iconoclasts, concluded with one final anathema:

"If anyone rejects any ecclesiastical tradition written or unwritten, let him be anathema!" (Richard Price, trans., The Acts of the Second Council of Nicaea (787), vol. 2 (Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press, 2018), p. 660).

Obviously, not all traditions would be included here. One often hears that there are big "T" traditions, and small "t" traditions, and depending on how one applies this distinction, it could be useful, but it certainly has been used to discount legitimate Church tradition. Broadly speaking there are four kinds of traditions in the Church (apart from Scripture itself, which is part of Tradition, even though we usually speak of it as being distinct from traditions preserved outside of Scripture): Apostolic Tradition, Ecclesiastical Tradition, traditions which may or may not be true, and local traditions, which are either local practice or local customs. Apostolic Traditions are without doubt binding and authoritative. The same is true for Ecclesiastical Tradition, when we are speaking of Traditions embraced by the whole Church.

When we refer to local practices or customs with the word "tradition," we are not talking about either Apostolic or Ecclesiastical Tradition. These may have some authority on the local level, but that is another matter. Also, we sometimes might speak of something being "a tradition" in the sense that this is something that has been handed down, but not in a way that we can attribute a great deal of authority to. For example, there is a tradition that St. Joseph of Arimathea and Christ visited England when Christ was a young man. Such a tradition may or may not be true, but no one is required to believe that this tradition is true.